By Julie Bourbon

The first time I went to Mexico on a border delegation, 20-odd years ago, I neither had nor needed a passport. We played with children in a colonia near an American electronics company’s maquila (factory) that we toured with a group of Catholic sisters and drank Coca Cola for days. All I knew then of Mexico was that you shouldn’t drink the water.

Earlier this month, as the political rhetoric around immigration in this country reached fever pitch, I accompanied a delegation of eight Mercy leaders and another Institute staffer to El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. We were there to bear witness to what my colleague Jean Stokan, who was also on the trip, might call the face of the crucified Christ among us.

And indeed, there he was.

In the story the young mother at the diocesan shelter told us about sleeping under the Paso del Norte Bridge for four nights, in the wind and cold, with just a foil blanket for protection. We, with our coats for the daytime and extra blankets for the night, had no idea El Paso could be so cold. She had only the clothes on her back, and a feverish, coughing toddler in tow. When they departed the shelter—fed, showered, bound for her father and brother in Maryland—it was warm outside, but the girl was zipped up tight in a donated pink snowsuit with a white faux fur-trimmed hood. Her mother was taking no chances this time.

The crucified Christ was there again in the form of a young woman who was taken to an ICE detention center and put in what the migrants call “Las hieleras,” or “the freezers,” group cells with no privacy and a lone toilet in the middle. She said the staff turned the air conditioning on full blast and blew talcum powder—a known carcinogen—through the filtration system because, they said, you’re just migrants, you’re dirty, no one wants you here. She told us, simply, “they did not treat us well.”

At 4 a.m. in the El Paso airport, the day we left, we saw the crucified Christ yet again as some of the migrants we’d met at shelters the day before were there as if to greet us, hands clutching immigration documents and boarding slips and their children’s hands, their faces strained with fatigue and bewilderment. We did our best to get them to their gates safely, and prayed that a kind stranger in Chicago or Newark or New Orleans would get them to the next place, and the next, and that they would be safe once they arrived there.

Everyone we met—Columban Fr. Bob Mosher, our tireless host; Columban Fr. Bill Morton, the brave pastor of Corpus Christi church in Juárez; the ageless duo of Sister Betty Campbell and Carmelite Fr. Peter Hinde at Casa Tabor; the quietly powerful Dr. San Juana Mendoza of the Cristo Rey medical clinic; Anna Hey and the other dedicated immigration lawyers at Diocesan Migrant & Refugee Services; Dylan Corbett of Hope Border Institute, who sheepishly asked for Sister Ana María Pineda’s autograph on his copy of her book, Romero and Grande; the impassioned staff of the Border Network for Human Rights; our energetic tour guide at El Paso’s Annunciation House, who came to know of their work because her twin sister had volunteered for a year there previously—has been as the face of Christ for migrants, offering welcome, compassion, a meal, a safe place to sleep, a ride to the airport, a prayer. For a few hours, in a basement meeting room turned clothing dispensary, did we, too, reflect the face of Christ to our migrant sisters and brothers?

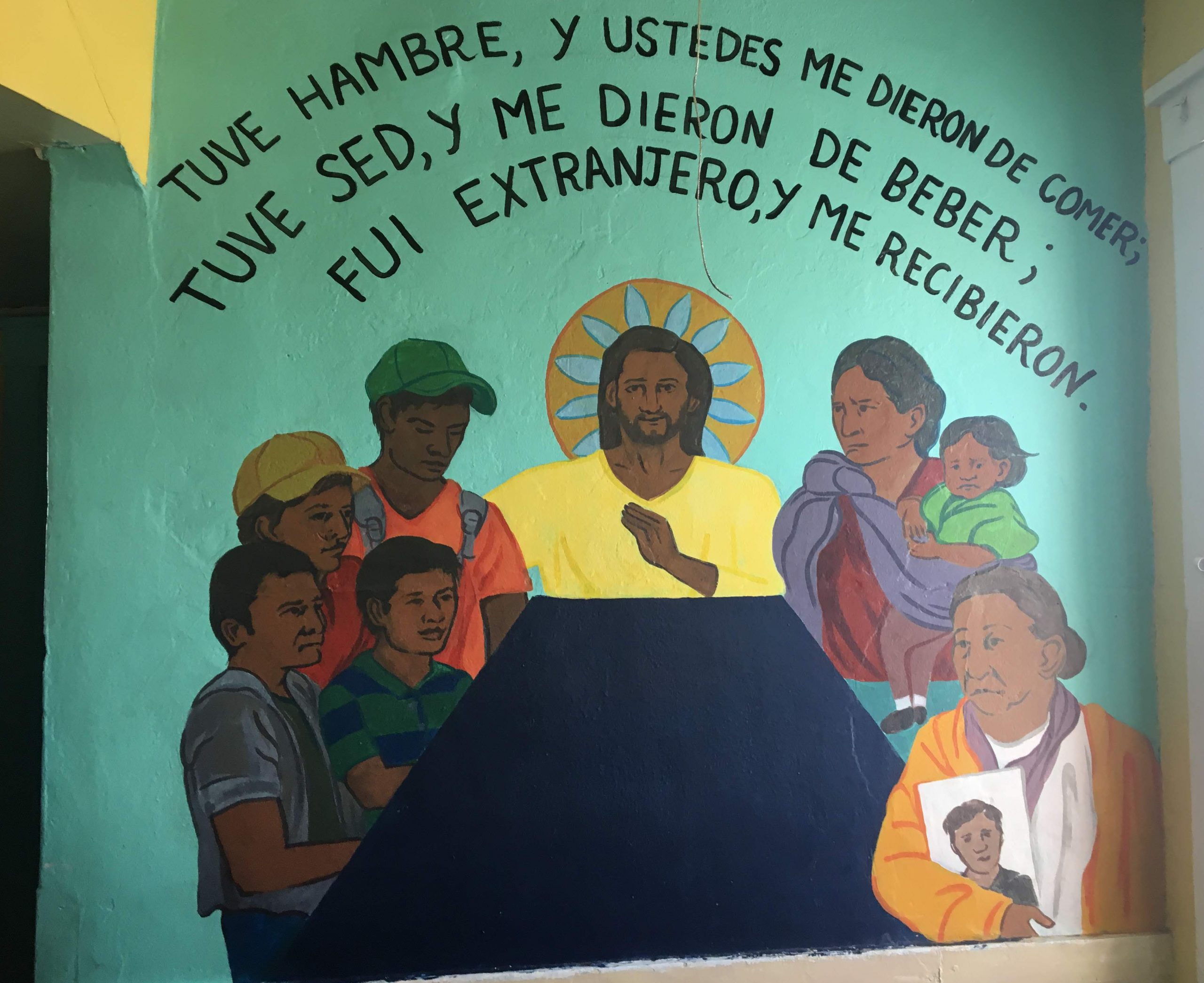

Painted on the dining room wall at Annunciation House, which has been serving migrants for more than 40 years, is a mural featuring the words of Matthew 25: “Tuve hambre, y ustedes me dieron de comer; tuve sed, y me dieron de beber; fui extranjero, y me recibieron.” I was hungry, and you gave me to eat; thirsty, and you gave me to drink; a stranger, and you welcomed me. Migrants painted it, and they painted Christ to look like them. Because he does.

If you are interested in learning more, click here.