Call to Prayer

We place ourselves in God’s Divine presence, deep within and all around us. We take a breath and breathe in the air that is essential for life and breathe out the dangers of polluted air. We place our feet firmly on the ground and hear the cry of Earth beneath our feet, her moans and aches from the cracks and holes that have been created below the surface and her cries of grief from the species that have been taken. We look around to those who are here with us and center ourselves in the cries of those whose voices may be muffled by the power and greed of our world. May our ears be opened to the cries, may our eyes be opened to the damage and may our hearts and minds be open to change. Amen.

An additional prayer resource is available here.

Exploring Extractivism

In answering the challenges of our times, we begin by listening deeply to the experiences of those traumatized and most impacted by extractivism and to our own experiences. We reflect and learn from these experiences by placing ourselves in a new light. The process of conversion begins when we experience the unexpected in ourselves and in the vulnerability of the other.

These inner and outward encounters unsettle our own habitual ways of thinking and acting. We begin “to see what we have made invisible.” In effect, when we become “seared by an experience,” we are compelled to change and to address systemic change. We realize that the small steps of our own conversion keep us personally engaged in larger collective decisions that are needed in a world where supply and demand shape the forces that entrap people who are most vulnerable.

Among the vulnerable are the rural Indigenous peoples struggling against corporate pollution of their waters, land and air; the economically impoverished urban people struggling to acquire daily food; and the refugees fleeing desperate situations often entrapped in border places. It cannot go unnoticed that most of these communities are Black, indigenous and other persons of color. Our Earth is among the most vulnerable, suffocating with explosive human consumption and multi-national greed.

This exploration of extractivism calls us to seek a more intense union with God through contemplative dialogue and through a cyclic process of conversion. In this kairos time, God asks us together to engage our prophetic voice. As we enter into this study, we seek to learn more about extractivism and the systems that maintain it, about its effects, and move toward a conversion that leads to common action. Through our prophetic collective action, we will challenge ourselves: How do we choose to stand together as a whole on the critical issue of extractivism?

Extractivism is a destructive and exploitative model of development that extracts natural resources on a massive scale, disrupts or destroys biodiversity, impacts global ecosystems, and devastates the health and well-being of local communities, while creating significant economic profits for the privileged few.

This process takes an integral approach, engaging us in three ways:

- Deep listening in which we hear personal and communal experiences that bring the effects of extractivism to life;

- Deep reflection on these experiences and on the root causes and effects of extractivism that is grounded in our theology and our social analysis; and

- Deep transformation as we discern how to act at this moment in time.

We will rely on intercultural and interdisciplinary lenses that shift power out of dominant Western worldviews and theologies. We will look to engage the whole body: mind, heart, flesh, hands and feet, understanding that knowledge is not located exclusively in the head, nor solely in facts and figures and scientific data. We are summoned to listen to the stories our whole body reveals to us. Even so, we cannot dismiss empirical data, as this information shows us what our bodies do not: the invisible poison in the crystal-clear river as it works its way down the mountain, the unseen toxins in the air that does not obscure our view of healthy trees, or the hidden contaminants in a deliciously crunchy apple.

We begin by listening deeply to experience, our lived reality and the lived reality from the perspective of peoples, communities and Earth impacted by extractive industries. Deep listening is listening with the heart. We move ourselves deeper by reflecting on these experiences. Deep reflection is letting go of preconceived ideas and norms so we are open to others’ ways of interpreting reality, which compels us to deepen our understanding of the root causes and real effects of extractivism. We will use the lens of eco-feminist theology of liberation rather than the dominant theological lens of the global North. This lens moves us out of the boundaries and dominations of Western analytical processes to include the wisdom, experiences and mediums – such as art, poetry, story and song – meaningful to those who live on the margins of society. The lens of an eco-feminist theology of liberation has risen from within the global south in its struggle against the interventions of the global north, and it will compel us to see differently.

By listening and reflecting deeply, we identify the ways we are called to respond. We engage God’s desires for a deeper communion between ourselves and God, a deeper communion with our neighbors, especially persons made poor by extractive industries, and a deeper communion with Earth and all of creation. Through this process, we are then called into Deep Transformation, a change personally, communally and corporately, to be in solidarity with and responsive to the needs of the vulnerable and marginalized.

This threefold process requires deep listening, deep reflection and deep transformation, and it compels us on both a personal and communal level to respond to God’s call for a new consciousness. It is not a linear progression, but a circular movement, going deeper by listening and reflecting, and coming back to our experience, and going yet deeper again as the cycle progresses through our conversation together and we come into a place of transformation.

Resistance to Change and the Power of Habits

Resistance to change, the power of habits and our support of exploitative systems are among the greatest hurdles we face as we seek to transform ourselves, our communities and our world. To effect real change, we need to understand and engage in change and transformation within ourselves while we seek systemic change and transformation in the world. We cannot challenge extractivism while in the same breath we support it through our daily habits and in our collective decisions. Fear and the complexity of the issue can paralyze our responses unless we follow the lead of those most impacted and their creative responses already underway to address the problems of extractivism. In short, there is hope and a way forward.

As Sisters of Mercy, we developed this material to renew our commitment to our Critical Concerns: Earth, immigration, nonviolence, racism and women. We invite you to join us in challenging ourselves on a daily basis to reflect on our habitual ways of thinking and acting, and at times, choosing to disrupt old habits and form new beneficial ones for the common good. We invite you to engage in this personal transformation when you pray, make choices about what you buy and how you live your daily lives and where you decide to collectively invest; when you educate yourselves and others in addressing these intersecting concerns; when you advocate with legislators and leaders; and when you invest resources to effect systemic change.

Deepening Our Commitment to Conversion

Two major environmental crises of our times unfolded in 2019-2020. In 2019, the burning of the Amazon rainforest, rightly called the lungs of the planet, accelerated. Driven by economic interest, land was and continues to be cleared for cattle ranching and for mineral extraction. The first highway built deep into the Amazon has paved the way for massive destruction of old- growth forests and substantial intrusions into the lands of indigenous peoples. The horrors perpetrated on the indigenous communities led to Pope Francis’ call for the Amazon Synod (October 6-27, 2019). Catholic bishops gathered to listen to the cries of the people who lived and worked in the Amazon. The Catholic Church found itself called to new paths of conversion.

Beginning in March 2020, we faced the unprecedented crisis of a global pandemic. The world was shuttered by a new coronavirus (COVID-19). Daily habits were disrupted, and we were compelled to learn new behaviors. While we were forced to stay home, Earth experienced a mild but measurable healing from our lack of activity. Reduced gas emissions worldwide resulted in cleaner air, bringing back views of our world once obscured in haze. But the behaviors we engaged in then did not all become new Earth-friendly habits once COVID subsided. And so, the warming of the planet continues on its trajectory.

The density of human population and its need for food and energy will intensify as the destruction of the natural world increases. Humans and their communities will persist in overstepping boundaries and encroaching on the habitats of wildlife. As a result, we will see not only the destruction of natural lands and forests as we have seen in the Amazon, but also a continual threat and a rise in frequency of more deadly viruses that originate when humans and domesticated animals “encounter” wildlife. Viruses such as MERS and SARS, and probably now the infamous COVID-19, have been linked to human encounters with bats. COVID-19 in its earliest phase threatened black and indigenous communities with alarming rates of infections and deaths. Viruses probably will alter our world even more in the years to come as climate change and human activity continue to disrupt ecosystems.

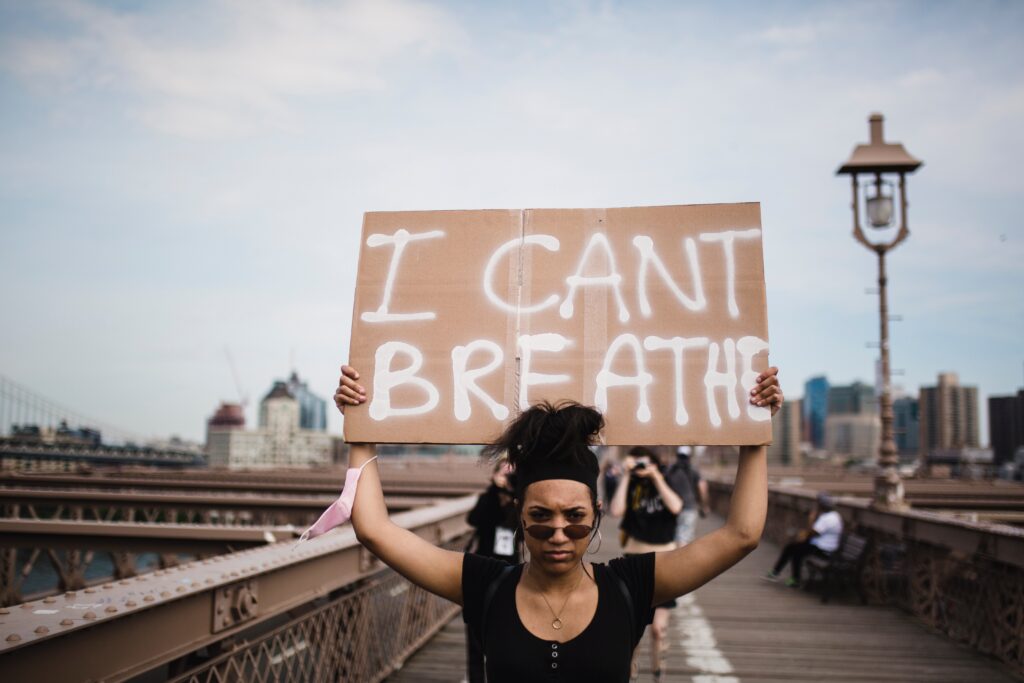

A third crisis, while not a new reality, challenges us. The Black Lives Matter movement has challenged longstanding systemic racism in the United States, and particularly racism perpetrated on Black communities. Racial violence fueled first by the historic brutality of slavery was followed by Jim Crow laws and lynching mobs that enforced systemic racism and racial segregation. The Black Lives Matter movement made visible the persistent forms of systemic racism still existing today, especially the inherent racism in our judicial and police systems. Environmental racism and racism embedded in financial structures and the extractive development model is seen when affordable housing and schools serving Black communities are located in old chemical- and waste-dumping grounds. In an area dubbed Cancer Alley in Louisiana, industries along the Mississippi River continue to decimate the health of Black communities. Underlying health conditions and lack of access to affordable healthcare surface are yet another effect of systemic racism. Black people died from COVID in disproportionate numbers. Thousands joined the Black Lives Matter movement to challenge these forms of structural, systemic and environmental racism.

As we struggle with the destruction of the Amazon and with the ongoing impact of COVID, and as we join in the challenge to address personal and systemic racism, we also face the unmitigated forces of extractive industries. Unrestrained extractivism takes many forms, and it affects the whole network of ecosystems, including our own. Extracting minerals and energy or extracting human labor, or extracting members of the community of life all severely disrupt and even eliminate ecosystems. They result in the poisoning of water, land and air and the displacement of whole communities. .

The most vulnerable especially Earth, laborers and the displaced are deemed expendable, with the greatest damage done to those already marginalized by race, ethnicity and money. Minerals and energy are not replenishable. There is no cycle of life, no planting and replanting as with the food cycle. There is only taking of Earth’s limited resources. With extractivism, ecosystems will continue to be radically changed, even destroyed, speeding up the climate emergency and its effects.

As we struggle to cope with the true cost of these challenges, we must engage in hard conversations and decisions and the reframing of our understanding. It is difficult to change values and habits and sustain new ones when we go it alone and are listening predominantly to the loudest voice and extractive industries who continue to make the business case for extractives. It is important to share in the process by which we challenge and change, but to do so in a way that inspires us. Such inspiration will keep us committed and engaged, while fear and anxiety will serve only to paralyze us.

We are in a new kairos moment. We are called to wake up or risk losing something indefinitely. This space of hope compels us forward so that we do not get stuck in a place of fear and anxiety. We begin by exploring the underlying values and inspirations that have already compelled us to change our habitual way of thinking and acting. We ask ourselves: What ways have we already changed and deepened our consciousness in favor of Earth’s health? In what ways have our current actions led to deeper changes?

Called to a New Consciousness: The Journey of Transformation

We long to live in right relationship with all people and with all of creation. This compels us to seek out a new way of seeing, a new consciousness. In this time, we are part of a global system that perpetuates the destructive effects of extractive industries along with their devastating impact on people, communities and Earth. The core business and the extractive development model of fossil fuel companies, mining companies and other companies focused on extraction of natural resources are inherently hazardous to people, communities and Earth. They have devastating impacts on water, land, air, biodiversity which has seen an 80% loss globally, and on the very life force of Mother Earth. It is a primary cause of our climate crisis. Respect for our interdependence with all creation is ruptured by extractive industries.

Indigenous peoples, who have lived for thousands of years in the lands of present-day Latin America, are victims of extractivism. They have experienced death threats, assassinations of beloved leaders and family members, and the destruction and poisoning of their sacred land, air and water. Whole communities have been forced out of their homes and land. Members of Black, brown and indigenous communities in the United States often must choose between their own physical wellbeing and their financial security when making economically disadvantageous decisions to leave an area where fossil fuel companies operate with no regard for environmental impact.

The call to a new consciousness by exploring and responding to extractivism is a challenging one. It requires us to move out of our habitual ways of thinking and acting, which for many of is us driven by Western thinking and economic models. It requires us to engage in new experiences that unsettle us and summon us to listen deeply to what stirs in us. And it calls us to critically examine the ideologies, prejudices and assumptions that inform our worldview.

Questions tug at our hearts: What makes it difficult for me to move out of my comfort zone? What keeps me there? What attracts me if I let go? What gives me joy in choosing differently? Whose stories do I not hear? What does a commitment to climate integrity ask of me at this time? It calls us to a more engaged solidarity especially with Black, indigenous and people of color, who are disproportionately impacted by extractives industries. It asks us to reclaim our interdependence and harmony with Earth and to understand deeply the devastating impact of extractive industries on the flourishing of the whole community of life.

The journey toward a new consciousness opens us in vulnerable ways so we can hear, center and respond to the cries of the poor and of Earth. In this journey of little conversions, we will find ourselves changing our habitual ways of understanding, thinking and acting. Systemic change does not begin with some grand transformation; it begins with a new understanding and these little conversions. While we move to claim our prophetic voice and prophetic actions, we remember that deeper transformation must be held and sustained by our solidarity with those most impacted by extractive industries, especially communities of color, and by an engaged and supportive community. This deep kind of transformation calls us to live together more conscientiously on an individual, communal and corporate level.

So how do we begin this journey toward a new consciousness around extractivism? And how will we empower our new consciousness through acts of solidarity with Earth and her suffering peoples?

Reflection Questions

As we begin, we will see what extractivism is and how it impacts people, communities, and Earth. The word “see” here connotes deep listening, a seeking to understand. Here we will de-center ourselves and listen carefully and attentively to the stories and experiences of those most impacted by extractivism. After deep reflection, we judge, that is, analyze what our response needs to be. Finally, we will determine how we might be transformed by what we have heard and learned. We discern how we might act in response to extractivism.

Start by reflecting on the following questions regarding personal and communal conversions that you have engaged in previously after hearing the cries of the poor and the cries of Earth. Take time to reflect on how far you have come, what compelled you to change and perhaps what holds you back from deeper transformation. Do you own personal reflection and journaling on these questions:

- Whose stories have you heard or read that have recentered your thinking towards the cry of Earth and cry of the poor? How have you found those stories?

- What concrete action have you committed to that changed a past habit or behavior in answering the cries of Earth (e.g., energy and water waste monitoring)?

- How have these changes called for a radical shift in how you live your daily life, such as an awareness of the amount of water used when showering or gas used when driving?

- How have these changes led you to acts of advocacy either through education or seeking policy changes in institutions and governments, responding to action alerts calling for just transition to renewables or campaigns to keep fossil fuels in the ground?

Next, continue by reading the expanded Definitions of Extractivism document.

- How do these definitions impact your understanding of extractivism?

- Take a few moments to journal your responses.