Walking with Saints at the Border

By Joanne Castner, Mercy Associate

A Mercy Border Immersion Experience in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, took place May 8-13, 2022. Following is one in a series of four reflections from a participant in the experience.

On May 8, 2022, 13 of us from across the United States gathered in the living room of the Columban Mission House in El Paso, Texas, the beginning of an immersion trip to meet with people who find ways to organize their communities and improve living conditions for those in need, and to discover why so many people from other countries are seeking to cross our nation’s borders.

Ruben Garcia, founder and executive director of Annunciation House, a network of shelters, has been helping migrants for over 40 years, providing them with safe housing and food until they are able to join their sponsors. Ruben meets regularly with Border Patrol, ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), and Homeland Security to learn when migrants are being released from detention and arranges for safe transport to one of the shelters.

From Carlos Marentes, director of the Border Farmworkers Center in El Paso, we learned about the difficult conditions Mexican farmworkers encounter. We learned how in years past, before Mexicans farmworkers were allowed to board the trucks which would take them to farms in the United States, they were required to strip and be sprayed with DDT. Carlos showed us a five-gallon pail filled with chili peppers; a farmworker earns 65 cents for each pail. In order to earn minimum wage, a worker would need to fill 100 buckets per day. He reminded us that food is sacred, and urged us to remember that the great majority of our food is harvested by undocumented workers who work in punishing conditions for little pay.

Border Network for Human Rights advocates for people on both sides of the border. Prior to 1996, the border was seen as a region, not two separate countries. People moved freely across the border for work, shopping and family visits. Then U.S. law changed, and now individuals crossing the border without documentation are criminally charged. A first violation is a misdemeanor; a second is a felony. The language around migrants has also changed—they are now referred to as “criminals” and “invaders.”

Anna Hey, an immigration attorney with the Diocese of El Paso, explained how broken our immigration system has become. Mexicans who were approved to legally enter the United States as of last month, had waited 22 years for entry. Due to the massive backlogs in our system, Mexican adults filing paperwork to enter the United States today will have a wait of at least 40-50 years before their cases will be heard. In some cities’ courts, more that 85% of immigration cases are approved; in others, less than 10% are approved. Since cases are judged according to the same federal laws, this discrepancy is disturbing.

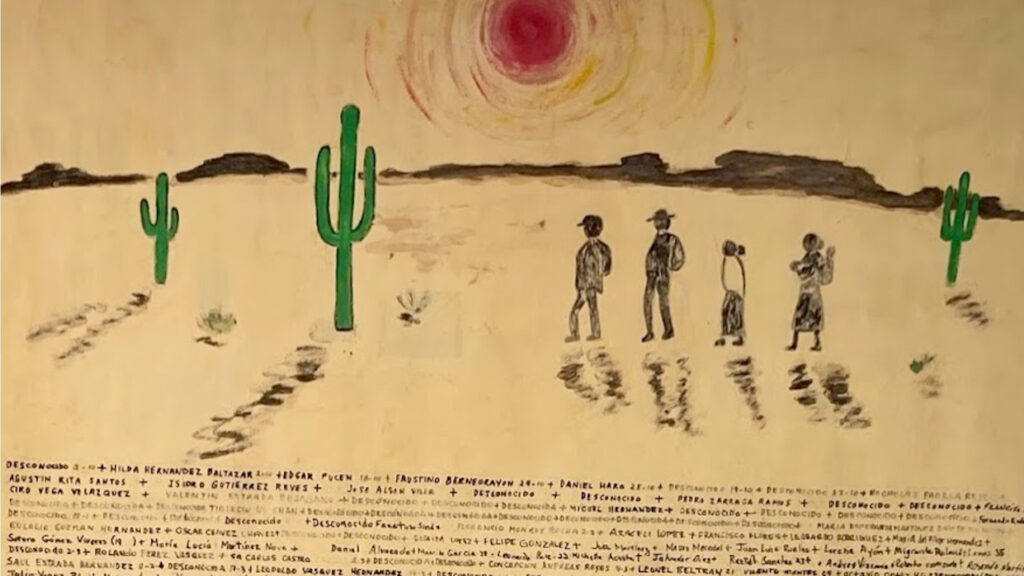

We travelled into Mexico to spend time in Juarez and Anapra, visiting a clinic for children with special needs; meeting with Father Bill Morton, who spoke of seeing a local village destroyed by the greed of a wealthy Mexican family; spending time with Sister Betty Campbell, who shared the memorial she has dedicated to those who have lost their lives at the border; and observing the razor wire fence on the International Bridge which prevents asylum seekers from setting foot on American soil.

For me, the most emotionally overwhelming part of this trip was our visit to the wall. We travelled to a barren part of the New Mexico desert, about 20 minutes west of El Paso. Before us, stretching from one end of the horizon to the other, stood a rust-colored behemoth of a structure, reaching 30 feet high. As we walked closer, a group of young children came running up to the fence from the other side, stretching their hands out towards us. Two little dogs ran back and forth through the slats of the fence. The children were standing in bare feet in an area strewn with trash, while the concrete block structures in which they lived stood some distance away.

Some in our group stayed and spoke with the children in Spanish, but I had to walk away. I was devastated by feelings of guilt and complicity that I, as a U.S. citizen, was in some way responsible for this atrocity of a wall. I wandered for a bit, then looked up at the mountain range nearby. To my right, the wall ran up and over the crest. To my left stood a tall white cross, erected years before by a missionary. Such a metaphor for good and evil!

I left with a broken heart, but also with deep gratitude to have met so many people at the border committed to doing whatever they can to make a difference in our world. My hope is to share the message of what I’ve learned whenever and wherever I can. In the words of my fellow traveler Kari, we truly did “walk with saints at the border.”

If you are interested in learning more, click here.