By Deborah Herz

“Well-behaved women seldom make history.” This quotation, attributed to historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, could have been written about the many Sisters of Mercy who protest social injustices and stand in solidarity with those who are poor and downtrodden.

One of these, Sister Ann Welch, once spent 30 days in prison for protesting the use of nuclear weapons. On October 3, 1983, she and seven other women, several of them vowed religious, cut through a chain link fence where missile tubes were stored at the General Dynamics Electric Boat shipyard in North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

“We spray painted the nuclear missile tubes with the words, ‘Thou Shalt not Kill,’” Ann says. “We were arrested and charged with breaking and entering and the malicious destruction of property. The judge in the case accused us of spitting on the Constitution.”

Ann willingly served her time in prison. Upon her release—and determined as ever to speak up—she and the women incarcerated with her held a press conference about the urgent need to provide education to the many women imprisoned at the correctional facility.

The former principal of Holy Ghost Elementary School in Providence, Rhode Island, Ann, now 86, says that even though she’s retired from attending marches and protests, she’ll never stop fighting for worthy causes.

“Even though nuclear missiles are still produced at the facility where we protested, I have no regrets,” she says. “Change often comes about slowly, inch by inch. But you have to be hopeful. You can’t get discouraged and throw in the towel. It’s a matter of conscience, and you have to do it. Protesting takes courage. It’s an opportunity to express Mercy through action. At first it’s frightening, but once you cross the line, you lose your fear.”

A Cry for Racial Justice

Thousands of demonstrators began marching in the streets of Minneapolis, Minnesota, on May 26 of this year to protest the brutal murder of George Floyd at the hands of police. In the weeks and months after, hundreds of thousands across the United States and abroad protested police brutality.

Their cries for justice came as no surprise to Sister Mary Jo Baldus, a music therapist in Winona, Minnesota, who lives only 130 miles from the spot where George Floyd was killed.

“It’s been brewing for a long time,” says Mary Jo of the nationwide protests against police brutality toward people of color that swept the country after Floyd’s death. “This was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Mary Jo participated in the Drive for Peace and Justice, a car parade and interfaith protest calling for an end to racial violence. “My niece and I joined other cars here in little Winona to call for an end to racial violence. We honked our horns and carried signs, and even though I’d like to think we made a difference, it’s not enough,” she says. “People are rightfully outraged. Racist policies have to change.”

Ann was equally affected by the murder, and her heart went out to the protesters.

“The looting and violence that occurred during some of these protests was shameful and unnecessary,” she notes. “But I think those who were brave enough to peacefully march, even though we are in the middle of a pandemic, are truly heroes. This is the cry, the scream, for racial justice.”

Mary Jo is heartened by the fact that police officers in many cities kneeled in solidarity beside the protesters. “Some of the officers even hugged the protesters,” she says. “That gives me hope.”

Yearning for Justice for Women

Hope is never far from reach for human rights activist and Mercy Associate Nelly Del Cid, who lives in Honduras. The sibling of Sister Masbely Del Cid, director of Casa Corazón de la Misericordia orphanage in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, Nelly began raising her voice against social injustices decades ago.

After Hurricane Mitch tore through Honduras in 1998, Nelly joined with the Sisters of Mercy to help Honduran women, who were left with the work of rebuilding the country. “Women were exhausted and depressed, and many committed suicide,” Nelly says. “The sisters looked for ways to respond to this, and the organization Mercy Dream Weavers was born to help women in poverty-stricken urban areas.” Mercy Dream Weavers is also located in San Pedro Sula.

When gang-related violence peaked in 2002, more and more Honduran women were murdered in brutal ways. “But we heard nothing from the authorities,” Nelly reports. “They were always blaming the victims. When we saw that this was not changing, we at Mercy Dream Weavers began to meet with other women’s organizations to talk about it. From there, we created the Forum of Women for Life and began to report what was happening.”

Today, the Forum is made up of 17 organizations represented by some 400 women. “One of our goals is to peacefully demand that the Honduran state implement policies and a budget that will eradicate violence against women,” Nelly says.

Though she is discouraged that violence against women is still all too common in many Latin American countries, Nelly, who calls herself “a peace worker,” will never give up the fight for justice. “Our most recent demonstration was on November 29, 2019, when we took over the principal entrances into the city of San Pedro Sula to demand justice for women,” she says.

This yearning for justice, especially for women, has always motivated Nelly. “To remain active in this struggle gives me much hope,” she says. “We continue to struggle precisely because there are political and social structures that escalate gender violence. We are committed to transforming these oppressive structures, so we will continue to use our voices to denounce injustice. The themes of justice, nonviolence and the care of our common environment nurture my activism.”

Though Nelly has never been imprisoned or personally threatened, she has been teargassed by the military while demonstrating. It didn’t stop her.

“I don’t give up because each woman who is murdered in Honduras is a warning that my life and the lives of my friends, my sisters and my family are at risk,” she says. “I don’t give up because I respond to the fundamental option to care for life, and as women we are the givers of life. I don’t give up because I know that women are not second-class citizens and our lives matter.”

Nonviolence as the Root of Social Change

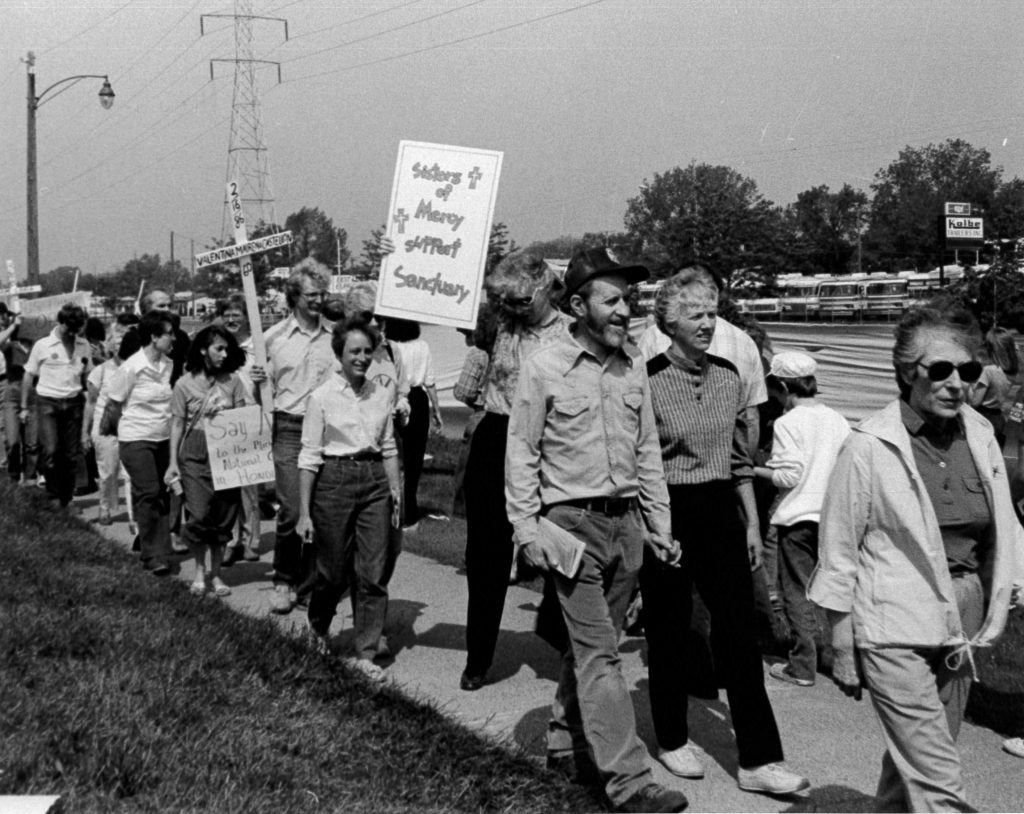

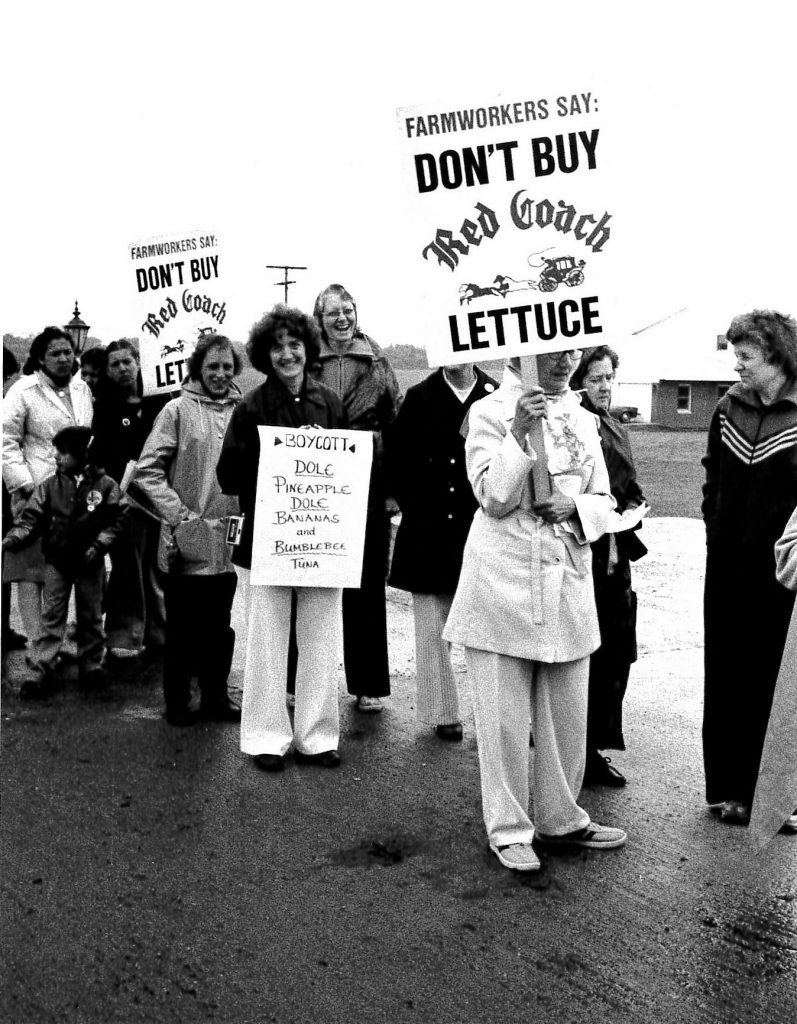

“Not giving up” are the watchwords of faith for many members of the Mercy Community. Historically, from their early days as walking nuns, teachers and nurses, the Sisters of Mercy have stood for social justice, especially for women and children. But actively protesting is a relatively new phenomenon for them.

“Though the traditional works of the Sisters of Mercy have always been ultimately oriented toward social justice, in the years after Vatican II, sisters were able to expand their works into modern social justice movements and protests,” says Betsy Johnson, collections management archivist at the Mercy Heritage Center in Belmont, North Carolina. “The earliest record of modern protest we have found in the archives—so far—was several sisters who attended the 1965 [civil rights] march in Selma, Alabama.”

Betsy notes that archival documentation includes anti-nuclear protests in the 1970s, the protests and action supporting the sanctuary movement in the 1980s, and protests of the U.S. Army School of the Americas (now the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation, or WHISC), which continue annually to this day.

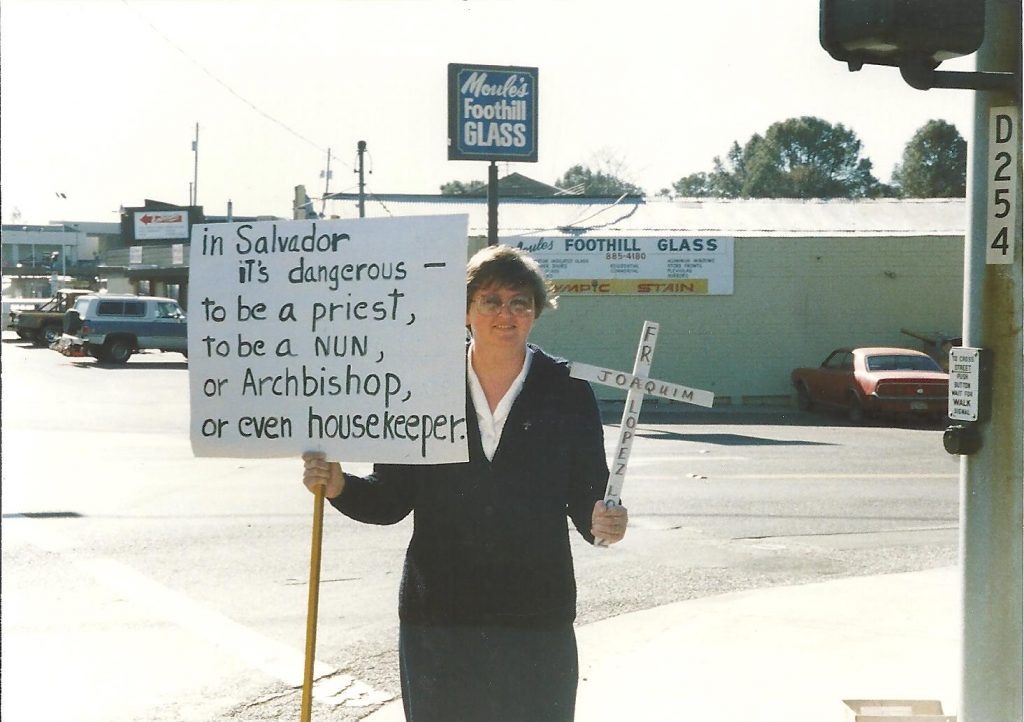

Sister Eva Lallo, who spent time in the late 1980s protesting the Contra Wars in Central America, says, “We really began getting our feet out the door after the Mercy Social Action Conference in the 1970s. We also called for justice after the cold-blooded murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero and the rape and murder of four churchwomen in El Salvador in 1980.”

With nonviolence as the focus, Eva, the director of development for Casa Corazón de la Misericordia, joined other sisters at workshops, where they learned to peacefully protest. “Staying in groups was always emphasized,” Eva notes. “There is strength in numbers. We were encouraged to lock arms, peacefully sing and pray, and not be belligerent or aggressive.”

Sister Eva Lallo, who spent time in the late 1980s protesting the Contra Wars in Central America, says, “We really began getting our feet out the door after the Mercy Social Action Conference in the 1970s. We also called for justice after the cold-blooded murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero and the rape and murder of four churchwomen in El Salvador in 1980.”

With nonviolence as the focus, Eva, the director of development for Casa Corazón de la Misericordia, joined other sisters at workshops, where they learned to peacefully protest. “Staying in groups was always emphasized,” Eva notes. “There is strength in numbers. We were encouraged to lock arms, peacefully sing and pray, and not be belligerent or aggressive.”

Whatever the cause, nonviolence has always been the basis for social change in the Mercy Community. “I was arrested while peacefully protesting the construction of a fracked-gas power plant in a pristine woodland” in Rhode Island, says climate change activist Sister Mary Pendergast. “My job was to plant tulips, but that didn’t matter. We were all arrested.”

While that was the first and only time Mary has been arrested, she’s been detained many times for many causes. “I still believe nonviolent resistance is the best way to effect meaningful change,” she says. “You won’t see immediate progress, but what is your option? You have to stand with people who are suffering.”

Since retiring 11 years ago from her career as a public school kindergarten teacher, Mary has devoted her time to fighting for the environment.

“I’ve lost count of the number of climate marches I’ve been to, and I’d go again tomorrow,” she says. “None of our Critical Concerns will matter if we have no Earth to live on. I won’t give up. Not as long as I can stand and walk.

Working to End Human Trafficking

Sister Jeanne Christensen is a founding board member of U.S. Catholic Sisters against Human Trafficking and the justice advocate on human trafficking for West Midwest. She believes it’s essential to speak out for justice and equality for all.

“In 2020, we have seen much violence and the results of oppression and truth suppressed,” Jeanne notes. “This calls for a loud raising of voices in protest and silent, prayerful solidarity. It is imperative that we raise our voices, whether through protests, shouting, TV interviews, signing petitions or letters to the editor.”

Jeanne acknowledges that fighting to end human trafficking or any social injustice takes courage, and that having the support of the Mercy Community is an advantage. For her, calling for justice is simply mercy in action.

“I learned two things from the first survivor of human trafficking I met in 2002,” she says. “First, it takes great courage to speak. And second, it takes powerful resilience to keep speaking when you are faced with oppression, suppression and sometimes violence in your effort to tell the truth.”

She adds a plea to all who would stand for justice and mercy.

“Please break your silence and raise your voice louder than ever before.”

Special thanks to the many sisters not included in this article who stand for social justice and speak out in support of our Critical Concerns. Grateful acknowledgment also to Sister Eva Lallo, for her Spanish translation, and to Betsy Johnson, for her archival research and photos.

Deborah Herz is a Mercy Associate and freelance writer working out of Narragansett, Rhode Island, and Naples, Florida. She can be reached at deborahherz@outlook.com.