By Heather Scott, Senior Director of Communications

I am a coward. I have never read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. I couldn’t finish Killers of the Flower Moon. I am a professional woman of white and consider myself an ally to the cause of all native peoples. And yet reading these stories was too painful for me. Ironic.

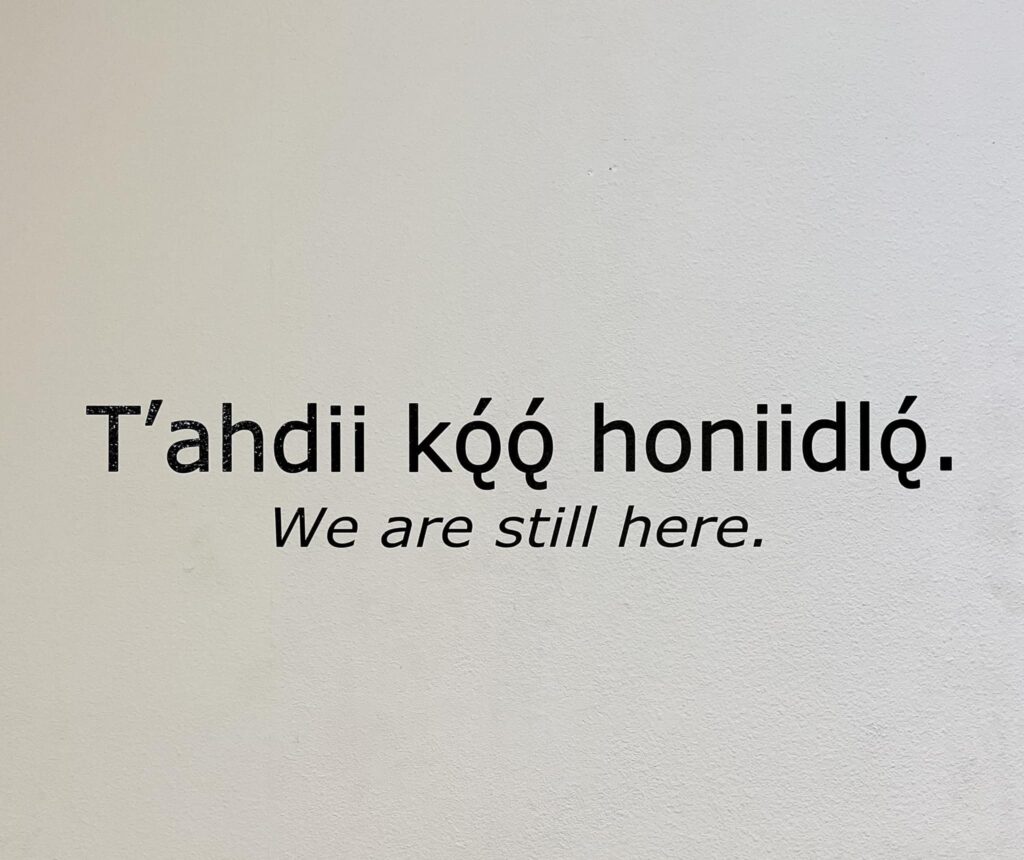

We cannot turn away from the painful legacy of colonization, especially on Indigenous Peoples Day, which rightly and belatedly celebrates the people the United States government tried to erase. They are still here. They are still struggling to tell their stories and to restore their land.

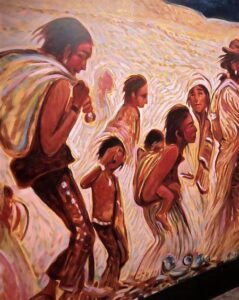

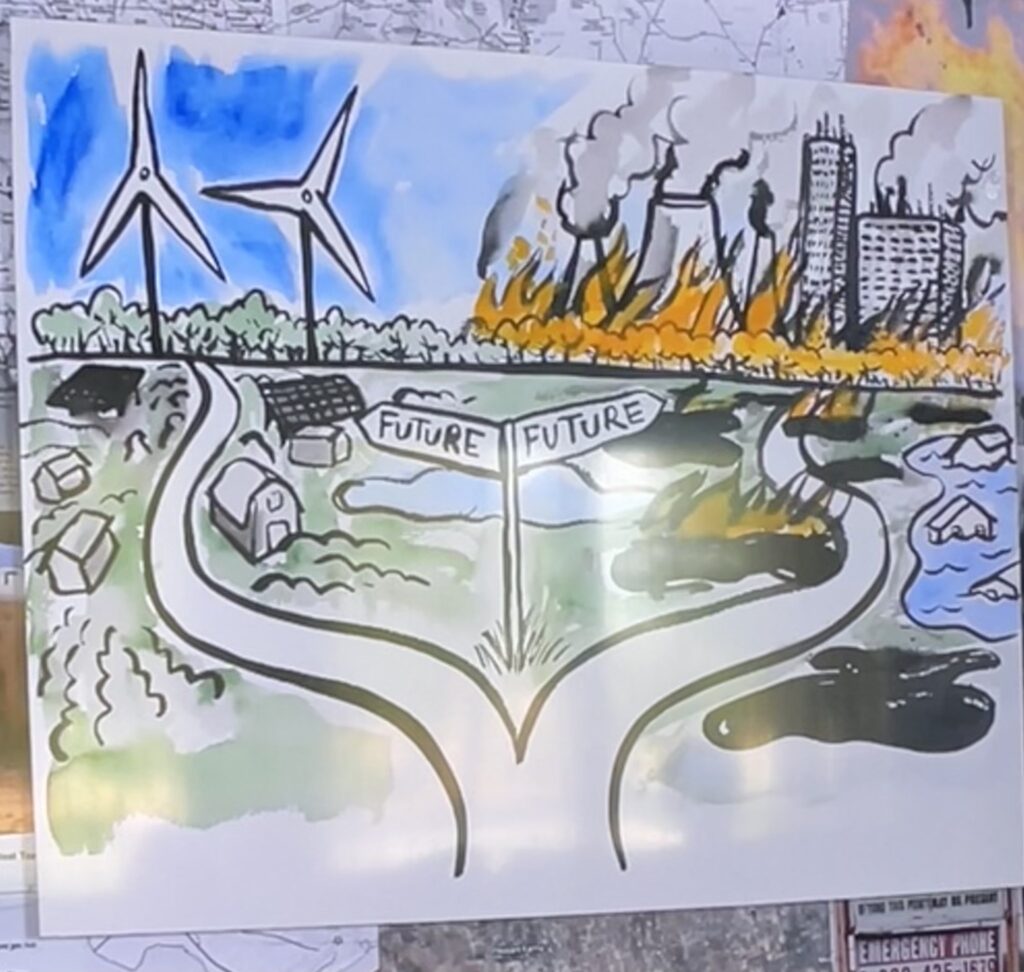

I recently journeyed on a pilgrimage through New Mexico, a state blessed with majestic natural wonders and jaw-dropping beauty, from the Rio Grande to Carlsbad Caverns. But there is an ugly story underneath that beauty. While on this extractivism immersion trip, we were privileged to visit the Navajo Nation and Laguna Pueblo and meet with some elders who shared their stories and their prayers with us. Not only did colonizers take their land, but they also turned it into a sacrifice zone, decimating it with uranium mining as part of the race to build nuclear weapons and a nuclear power industry. That industry has polluted the soil and the water. Little effort has been made to clean it up even decades later. As often the case in the history of Native Americans’ dealings with those in power, there has been a lot of talk but little action.

At Red Water Pond Community, we sat in the shadow of a mountain of uranium waste. It lies close to the site of the worst release of radioactive material in US history – the third biggest in the world after Chernobyl and Fukushima – and one you probably never heard of, although everyone knows about Three Mile Island which happened the same year. A Diné (Navajo) healer, who worked in the mines and was nearly killed there, blessed us with smoke and asked for forgiveness from Mother Earth for the damage done by the industry.

He and his sister continue to fight to ensure the survival of their village, just as thousands of Diné and Ndé (Mescalero Apache) refused to be wiped out after The Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, another largely forgotten story. We also prayed with two Pueblo women from the San Idelfonso and Santa Clara Pueblos. One brought two of her grandsons to share an offering. Those boys are the face of the future. They are the face of a people who survive and who continue to spread hope even amid an expanding footprint of the nuclear industry at Los Alamos, which looms over their homes.

The Diné traditionally value community over individual wealth and believe one must walk in beauty, in harmony with Earth and with each other. This prayer from the blessingway (Hózhójí) ceremony holds a message for all:

In beauty I walk

With beauty before me I walk

With beauty behind me I walk

With beauty above me I walk

With beauty around me I walk

It has become beauty again.