On August 18, 1920, the United States Congress ratified the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, recognizing women’s right to vote. That victory did not come easily. It required hard work on the part of many women’s rights advocates and the men who supported them, and it narrowly squeaked through the final vote.

My dad was born in the United States in 1900, but he grew up with stories from grandparents and great grandparents about the days of penal laws in Ireland. Catholics, male or female, had no vote and were restricted from participation in society. They could not attend university, own property or practice their faith publicly. That heritage left him with two strong convictions: as free people, you go to church and you vote. He passed on those principles as moral imperatives to his three daughters from our earliest days.

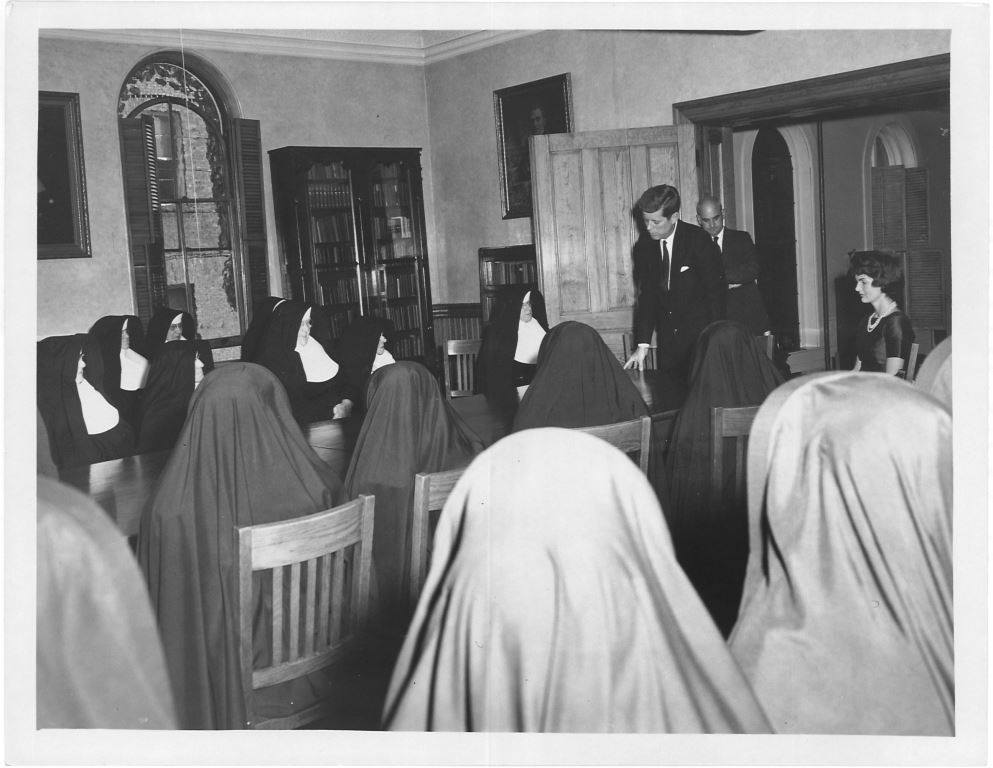

In my youth, the age of eligibility for voting was 21. The first time I was able to exercise my right to vote was 1960. I was in Mercy novitiate by then, and eager to vote. The Democratic candidate was John F. Kennedy. Daddy’s dream was fulfilled that year—we could cast a ballot for an Irish-American Catholic as president of the United States! I’ve voted in every election since 1960.

Aside from the coming-of-legal-age satisfaction of that first time, my most memorable voting experience was the 2008 election of President Barack Obama. I felt a personal sense of achievement, as well as a great amount of hope for the future in the outcome of that election. I’d marched in Selma in 1965. There, I met Black Alabamans who had never been allowed to vote, including a former U.S. marine who earned a purple heart at Iwo Jima. I was embarrassed and sad that I, a young white woman, could vote and they could not. Passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1968, 50 years after the passage of the 19th Amendment, followed Selma as another hopeful affirmation of democracy. Those experiences seemed directly linked to President Obama’s victory in 2008.

As we face the 2020 elections, two problems challenge my 1968–2008 hopefulness.

First is the fact that in 2013, a Supreme Court ruling abrogated much of the Voting Rights Act by deeming federal legal protection no longer needed because poll taxes and qualifying tests are gone. Those who would restrict the rights of minority voters have adopted new, more sophisticated but equally despicable methods: gerrymandering voting districts; moving around polling sites regularly so voters can’t find them; intimidating voters through fear, crowds and long lines; disqualifying ballots in minority neighborhoods; and circulating false narratives about voter fraud to undermine trust in the process.

Second is the fact that our political system is currently dysfunctional. Paralyzing polarization, a loss of a sense of the common good, the prevalence of racism and bigotry, voter apathy, nationalistic isolationism and incompetent leaders—these are among the elements bringing us to the edge of our ability to sustain democracy. In the last two election cycles, this dysfunction prompted too many people to conclude, “I don’t like either candidate, so I just won’t vote.” That is a dangerous cop-out which does nothing to address the problems. It betrays our ancestors who labored to secure the right to vote for themselves and us. It betrays Mercy’s legacy of serving “the poor, sick and ignorant” via social responsibility.

Come November 3, 2020, I’ll observe the centenary anniversary of the 19th Amendment by voting. I’ll do so in loving loyalty to my dad’s wise counsel, to my Irish ancestors who were denied that right and to the women who brought about the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment. I’ll vote in solidarity with the generations of Black Americans prevented by law from voting. Animated by the Catholic social teaching principle of quest for the common good and the urgency of that quest today, I’ll vote for a candidate whom I can respect, whose ability to work toward restoring and stabilizing our democracy is assured, whose record of integrity is lifelong and whose compassion for everyday people is genuine and to be trusted.