Facing fears amid uncertain times, Sister Mary Waskowiak walks with migrants

By Catherine Walsh, Senior Writer

Coffee in hand, Sister Mary Waskowiak takes her seat on a meditation cushion the morning after the consequential U.S. presidential election. She and four other women sit silently in the chapel of Casa de Misericordia – the House of Mercy – in San Diego, California, contemplating the election’s meaning for their migrant friends and for their ministry.

One woman is sprawled on the floor, as if imploring the heavens for help.

After 30 minutes Sister Mary strikes a gong. She and the others begin talking in anguished tones about the question uppermost in their minds: What will become of immigrants under a president who promised to carry out “the largest deportation in history”?

“Of course there’s fear,” Sister Mary said later that day.

She began her migrant ministry is a response to God’s call, she explains. On her 70th birthday in 2018 she asked “the Holy One” what she should do with the next decade of her life, a question that surprised her because “I don’t usually think in terms of decades.”

“There was no answer, no lights, nothing, so I just made a note of it in my journal.” But nine months later, Sister Mary heard a voice during her quiet time saying, “I want you to go to the California-Mexico border.”

She chuckles softly as she remembers her response. “Forgive my language but I did say to God, ‘Well, what the hell does this mean?’”

It meant that Sister Mary, an extrovert who had spent decades serving in leadership with the Sisters of Mercy and the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, “talked with anyone who would listen” about how she could respond to her religious order’s 2017 directive “to act in solidarity with migrants, immigrants, refugees and victims of human trafficking, seeking with them a more just and inclusive world.”

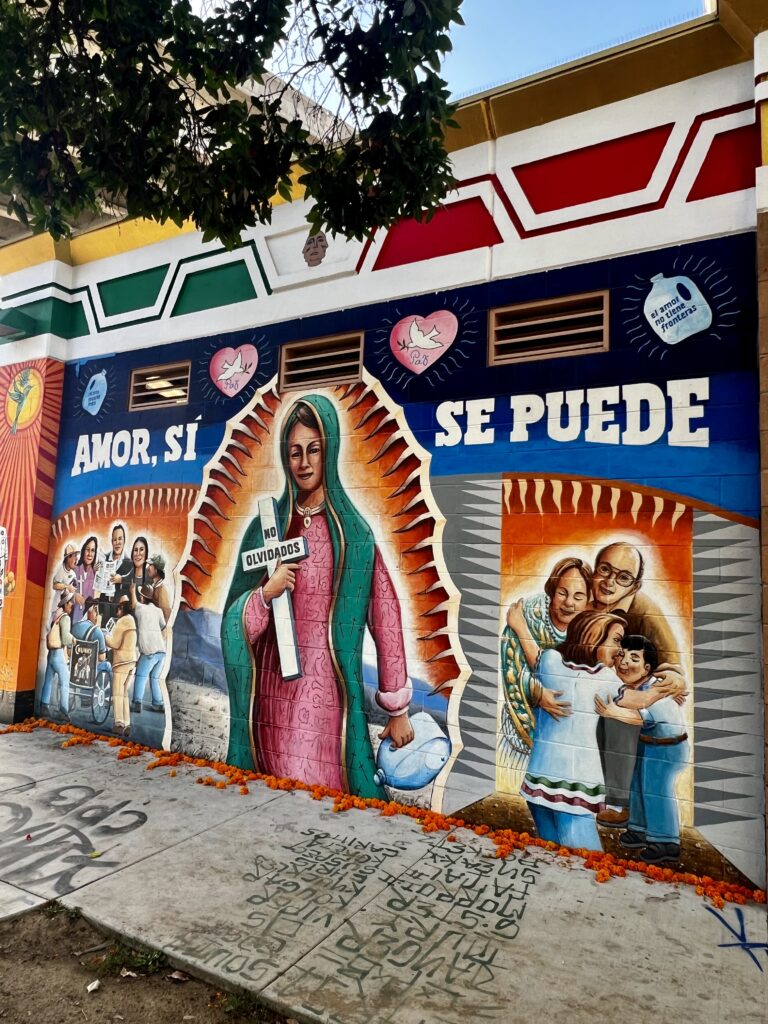

Those conversations led her to the Jesuit parish of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the Barrio Logan neighborhood of San Diego, where she eventually moved into the parish’s former convent with two other Sisters of Mercy, a Franciscan sister and two laypeople—a woman and a man. “We are an intentional, inclusive community dedicated to the migrant person,” says Sister Mary.

Over the last four and a half years 12 religious and lay people have joined the community, some for as little as six months and some who are still there. The community’s inclusive nature allows for creative responses to the needs of the times, “something the Sisters of Mercy have always been known for,” Sister Mary says.

The border is 12 miles from Casa and community members initially planned to focus their efforts there. But the border’s closure during the pandemic led Mary and her Casa friends to hold listening sessions with three women the pastor called “the queens of the parish” about the pressing needs of the church and the neighborhood, where about one-third of the mostly Hispanic community is undocumented.

These sessions led to the opening of a community resource center at the church that offers social services, a monthly food distribution, material aid to those who need it and support to immigrants. Casa members also started a Healing Wounded Hearts program for those who have experienced trauma, English-language classes, legal assistance through a Mercy Justice Immigration Project, a community garden and border immersion/service-learning experiences. These efforts receive support from the Sisters of Mercy Ministry Fund, which provides financial help to many Mercy ministries worldwide.

When about 1,400 migrant girls between ages seven and 17 were housed at the San Diego convention center in early 2023, Sister Mary and Sister Mary Kay Dobrovolny, a founding Casa member who now serves as director of new membership for the Sisters of Mercy, were among those who responded. They provided pastoral care and helped with any task at hand, from distributing food to opening boxes of donated rosaries and other goods.

One day Sister Mary watched as a group of girls were “jumping into the boxes of rosaries, holding them up and choosing among the different colors and the styles of crosses, and then putting them over their heads.” One girl selected some rosary beads and then came to her and stood in silence, tears streaming down her face. “I felt so helpless,” Sister Mary recalls. Talking with the girl in Spanish, Sister Mary learned that she was from El Salvador and asked if she could touch her. The girl nodded and Sister Mary placed her hand on her forehead, saying in Spanish, “May you be blessed in peace.”

When she turned around, there was a line of girls inclining their foreheads toward her. “I had to bless every girl.”

These days Sister Mary provides practical help to young migrant families from Ecuador, Venezuela and Peru, assisting them with legal challenges, health care, housing and financial needs. In addition to her direct service, she’s involved with efforts by religious sisters in a dozen different orders on both sides of the border who work to change systems and policies that lead people to migrate. “I am growing in my passion for systemic change that gets to the roots of the reasons the people leave, including drugs, cartels, extreme poverty, climate change and gangs.”

In the aftermath of the presidential election, Sister Mary is grateful that California’s Governor Gavin Newsom and the State Legislature are working to protect migrants. But little things worry her as a sign of what may be coming: a woman who wouldn’t take a bus to meet with her out of fear of being picked up by immigration officials; a parishioner attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in an affluent neighborhood who was asked “When are you leaving the country?” When the parishioner returned to the AA meeting the following day, the same man asked, “Why are you still here?” Sister Mary shakes her head sadly and exclaims, “That is so against AA principles!”

But come what may, she and the other Casa members will continue their ministry with migrant people, working in the coming months with the pastoral team of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church to open a center for migrant women and children. For over a year, the parish has provided shelter and meals to migrant men in a Quonset hut on its property and recently women and families have been staying there.

“I am haunted by an old quote that says, ‘Mercy responds to need that’s known; the greater the need, the greater the response,’” Sister Mary said. “Accompanying migrant persons will continue to be my calling no matter what the future holds.”