These blogs are part of a series of reflections on the conditions at the U.S.-Mexico border. As long as we are called to respond with mercy to our migrant sisters and brothers, we will continue to pray and act on this Critical Concern of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas. Read other stories of Mercy on the Border here.

By Sister Mary Bilderback

A poem haunted me on my recent trip to the border.

W. H.Auden takes Brueghel’s painting, The Fall of Icarus, as the subject for his poem, “Musée des Beaux Arts.” If we didn’t know the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, there is in the painting an odd detail in the lower right corner—a pair of legs plunging into the sea. They could belong to a farmhand cooling off after a hard day’s work, or a boy playing hooky on a sunny afternoon. It is a pastoral scene complete with ploughman and horse, shepherd with sheep, all going about their lives, as a stately merchant ship stays its course nearby.

But we do know the story and we know that just beneath those white legs are fantastic wings fashioned from twigs and feathers and wax, and the longing to be free.

The Greek myth is about a father and his son risking their lives to escape a tyrannical king who imprisoned them in a labyrinth. There is no way out of this maze but up. Inspired by birds, they craft wings to avoid certain death that awaits them if they remain behind. In flight they get separated. The boy flies too close to the sun. The wax wings fail.

In his poem, Auden amplifies the splash that Brueghel suspends between life and death:

“About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters: how well they understood Its human position: how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along…” (9 lines omitted)

“In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.”

W.H. Auden, Collected Poems, New York, Random House, 1976. f

It is the job of metaphor to haunt us. It can move us from the comfort and suffering of our singular lives to the place where all lives begin—as one mysterious communion.

Just before Thanksgiving, a group of us from five states and Washington, D.C., traveled to the U.S.–Mexican border—an imaginary line, 2,195 miles north of the equator—neither demarcation our astronaut friends claim to be able to see from even shallow space. Nonetheless we touched it—a substantial barrier, built on a flimsier concept and reinforced with spool after spool of chicken and razor wire, staring deadly serious in both directions, while white plastic grocery bags spiraled all around—up and over, back and forth across the wall like flocks of vultures.

We went because we wanted to visit the children being held in the detention camp at Tornillo, Texas. We wanted to know what a day in their upset lives looked like; who was caring for them; whether they could play and pray and sing; what they were learning.

Our group was organized by the Justice Team of the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, and grace-fully hosted by Fr. Bob Mosher at the Columban Mission Center in El Paso, Texas. We were strangers who became friends—an ad hoc community formed around a heart-binding, hand-extending mission.

We sat together in silent meditation every morning. In the evening we shared the gritty details and raw reflections of what we had witnessed that day. We shared meals, poems, chores and laughs. We borrowed each other’s strength and practiced each other’s courage. Someone quoted someone wise, saying “What we alone can do we cannot do alone.”

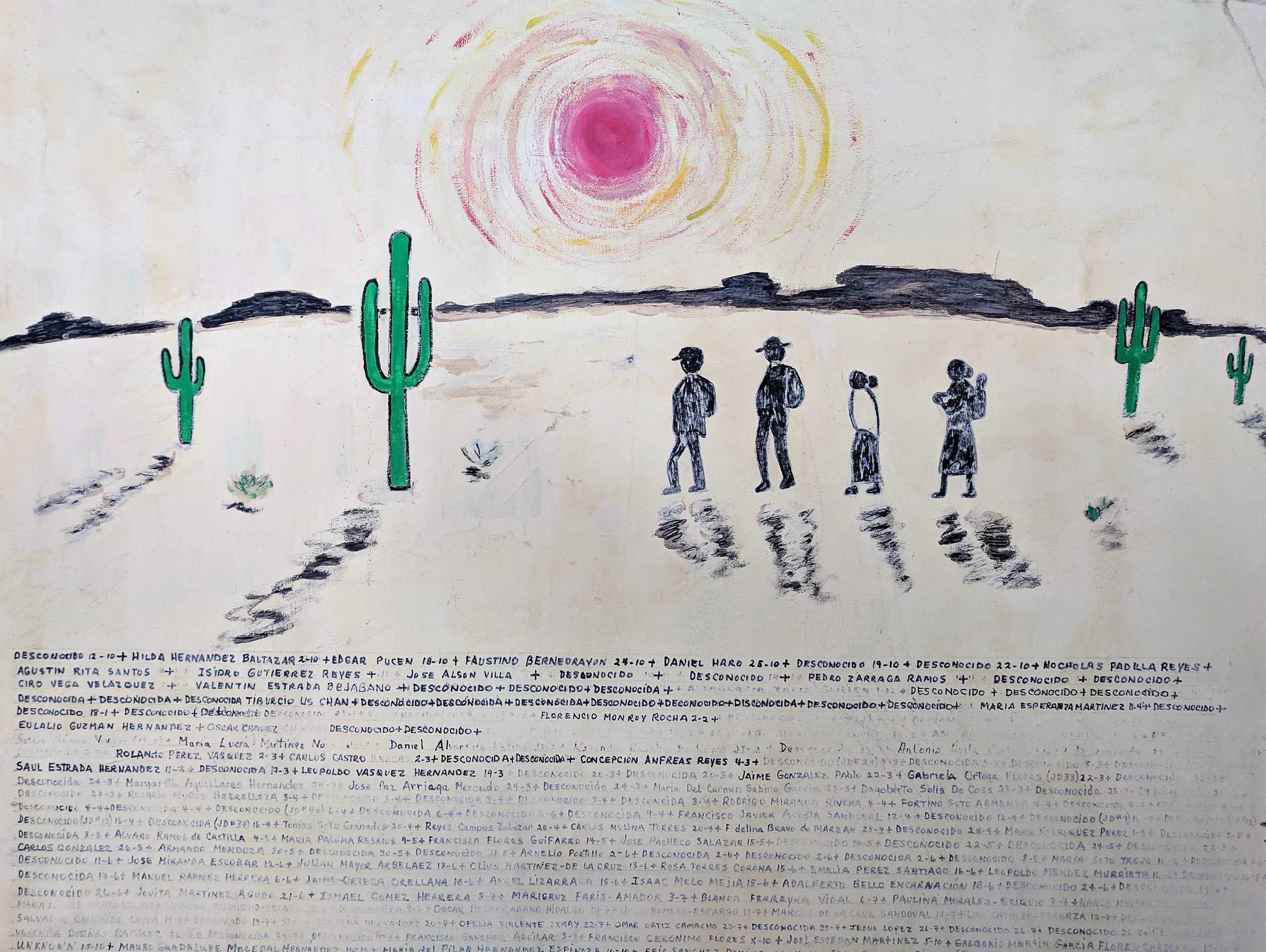

One morning we walked across the Santa Fe Bridge into Juarez, Mexico. We visited the remarkable clinic of Dr. San Juana Mendoza and a church in Anapra decorated by parishioners for the day of the dead with crosses made of salt, lying in beds of orange marigold petals, like reflecting pools before the altars. Sister Betty Campbell and Fr. Peter Hinde welcomed us into their sanctuary home surrounded by hand-painted murals remembering the tens of thousands dead or disappeared—lives lost to poverty and violence—souls who had touched their souls. We walked back across the bridge that night, heavy, with more questions than we had come with. In El Paso we spoke with border patrol Agents and a lawyer at the office of Diocesan Migrant & Refugee Services in El Paso. Our questions deepened.

On the morning we were to take part in an interfaith vigil being held just outside the camp at Tornillo, we stopped at a convenience store that sold everything from socks to nuts. We bought snacks—salty almonds and soda. Coke was safer and cheaper than water. And on a normally forbidden whim, we bought a bunch of red heart-shaped balloons, for the children—sort of a message in a bottle we hoped they would discover drifting across the desert sky, echoing the mantra we would be kept from delivering: “No estan solos. You are not alone.”

When we arrived at the camp, it was, as we expected, off limits. From drone photos we knew it was a maze of tents, symmetrically arranged in the middle of nowhere. Dusty cotton fields further obscured its presence and absorbed the noise of its very existence. Shiny white buses with covered windows traveled in and out of the sequestered compound. The only other traffic on the road that day was an endless parade of tow trucks hauling trashed cars to a junkyard just across the border in Mexico.

Young students, rabbis, musicians, nuns, artists, priests, educators and grandparents took part in the vigil. We sang and prayed and thought a lot about why children and families would run away from home. We got as close as we could to the tents chanting, “No estan solos,” but inside the tents, loudspeakers drowned out our voices. We never saw the children, nor they us. We never learned what was happening inside those tents. We were there to witness, not for civil disobedience that day. We released the red heart-shaped balloons and left.

Our group has been back for almost two months now. I, for one, am having trouble getting back on board my “expensive delicate” life. Maybe I should go back. Maybe I should have stayed home.

But now there’s good news comes from Joshua Rubin, who has kept vigil outside those tents for months: the camp at Tornillo is closing. The children will go on to family. I’m grateful we went.

The trip continues to haunt me. How shall I live?

Our sisters and brothers are fleeing their homelands—all over the planet. Why?

Should we be fleeing ours? Where shall we all go?

We’re seeing something amazing.

There are children falling out of the sky!

We tremble.

We do not turn away.