By Marianne Comfort

The Mercy community is taking to heart Pope Francis’ call to “ecological citizenship” through changes in lifestyle and policies that exemplify its Critical Concern for Earth and the sustainability of life.

Mercy-sponsored hospitals, colleges and universities are leading the way, with campus-wide initiatives to reduce carbon emissions, keep plastic out of landfills, conserve water and implement sustainable food practices and land management.

In fact, results of a sustainability survey conducted by the Extended Justice Team throughout summer and fall 2018 show that most convents, administrative centers and Mercy-founded and -sponsored ministries and institutions are implementing at least some “green” initiatives.

Karen Flake, president of Mount St. Mary Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas, summed up what is a common motivation for many: “We desire to use our resources wisely and share with all citizens of the world,” she said. “We recognize that many people in our country can afford an abundance of resources while others both here and elsewhere live in unsanitary or poor conditions.”

Her school, after an energy audit about two years ago, has been replacing lighting, heating and cooling systems with more energy-efficient versions. They also are using webinars for some staff development sessions and conducting board meetings by telephone, to reduce travel. And like many schools that took part in the survey, they are reducing plastic waste by promoting reusable bottles and installing water bottle refilling stations.

Efforts Large and Small

While such efforts on their own won’t solve the climate and environmental crises, they are important steps to take in conjunction with advocacy for large-scale government action.

In his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’, Pope Francis wrote that “there is a nobility in the duty to care for creation through little daily actions.” He added that, “we must not think that these efforts are not going to change the world. They benefit society, often unbeknown to us, for they call forth a goodness which, albeit unseen, inevitably tends to spread.”

Ninety-nine convents, administrative centers, institutions and ministries participated in the survey. Their reported efforts include St. Joseph’s College of Maine’s goal of becoming a carbon-neutral campus by 2036 and its already operational recycling and composting programs, water-conservation efforts and revolving loan fund to finance new sustainability initiatives.

They also include the commitment of Sisters Margaret Park and Patricia Tyler of the Rural House of Mercy in DuBois, Pennsylvania, to share a car, remove air conditioners from the old rectory they live in, grow their own produce and purchase as many locally made products as they can, from meat and organic soap to Christmas gifts.

“All of this saves on the energy that goes into long distance transporting of goods,” Margaret said of their purchasing philosophy. “And it builds wonderful relationships with the local people.”

What follows are just some examples of how the Mercy community is adopting a wide range of environmentally sustainable practices and policies.

Managing Facilities for a Healthier Planet

Mercy Circle, a 110-unit retirement community outside Chicago, was built with sustainability in mind, earning LEED “green building” certification, one of 14 LEED-certified buildings reported by survey respondents around the Institute.

“Keeping the planet safe and healthy is just an extension of our core mission” as caretakers, said Mercy Circle Executive Director Frances Lachowicz.

Features include energy-saving light fixtures, high-efficiency windows and heating and cooling systems, low-flow toilets and plumbing, native plants to reduce the need for watering, and a light-colored roof with vegetation and permeable concrete pavers in the parking lot to reduce storm-water pollution. The facility also has bike racks and showers for employees, to encourage cycling to work, and preferred parking spaces for low-emitting and fuel-efficient cars.

In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Mount Mercy University is among the 63 percent of survey respondents minimizing environmental impacts through groundskeeping practices.

Sustainability Director Rachel Murtaugh said they have installed two rain gardens that will intercept about 70,000 gallons of water each year. (The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that pollutants carried by rainwater runoff account for 70 percent of all water pollution.) The campus is introducing native plants that require less maintenance and watering, and creating a habitat for pollinators and native birds. The groundskeeper uses an ice-melt that doesn’t salt the soil and kill the grass, and Murtaugh said she’s looking into the environmental impacts of pesticides and fertilizers used on campus.

Cutting Energy Use

More than two-thirds of respondents reported installing LED lighting and/or replacing heating and cooling systems for greater energy efficiency, while only 28 percent have budgeted for purchasing renewable energy or installing solar panels, which often don’t begin to pay for themselves for years. Still, many sisters and staff said they’d like to learn more about transitioning to renewables, and the Northeast Community would be a good place to seek inspiration and practical advice.

Mercy Farm Eco-Spiritual Center in Benson, Vermont, received a grant from Green Mountain Power to cover half the cost of purchasing 20 solar panels to install on the barn’s south-facing wall, to capture the most sun. “It takes a long time to repay your investment in solar—maybe 10 years,” said Sister Betty Secord, co-director of the Eco-Spiritual Center. “But the mission of Mercy Farm is to be environmentally sustainable, and this is a step towards that.”

In 2018, the farm’s solar panels produced a total of 5,466.99 kilowatt hours of energy and a carbon offset equivalent to 97 trees.

In Albany, the Northeast Community’s Real Estate Portfolio Director, Dan Justynski, investigated ways to save energy without covering the beautiful roof at the Convent of Mercy. Sister Kathleen Pritty directed him to Hope Solar Farm, hosted by a United Methodist church in nearby Troy, New York.

The community has entered into a contract with the farm, which is expected to start power generation this year. The convent will receive energy through the local utility company and then be reimbursed for its portion of solar energy put back into the grid. If usage remains constant, Justynski expects that the convent will save $10,000 per year.

“We are thrilled to partner with others to do our part in protecting Earth and its natural resources,” Sister Patty Moriarty of the Northeast Community Leadership Team said of these and other major sustainability efforts, which include putting into conservation more than 200 acres of property around their offices in Cumberland, Rhode Island.

The Saint Ethnea School in Buenos Aires, Argentina, took a different approach to renewable energy by engaging young people to build a solar hot water heater as part of their physics curriculum.

Students spent about six hours constructing the first prototype with mostly recycled materials, resulting in a heater that brought the water to 113˚F/45˚C on one day of sun in the middle of winter. Participants learned that a typical family could save approximately 30 to 40 percent of the energy needed to heat the water for washing and bathing in the winter, and closer to 100 percent in the summer, said school Director Josefina Gourdy Allende.

The school expects the students to share what they’ve learned with low-income households that could most benefit from the savings of building their own hot water heaters from materials on hand. “It is not a matter of building a thermal heater to give it to someone who needs it,” Gourdy said. “Rather, we aim to create an encounter of brothers and sisters in order to live a little better in ‘our common home,’ so that someone else can enjoy a hot shower.”

The Sacred Right to Water

Treating water as sacred and a human right is clearly a value at many Mercy properties. Nearly all survey respondents reported some form of attention to the use of water, whether through education or by installing low-flow toilets and/or showers or water bottle refilling stations. Only 15 percent reported having a formal water audit completed to assess usage and plan for conservation.

In St. Louis, a small reflection group chose water as its focus for the Mercy International Reflection Process in 2016, part of discerning a response to the cry of the Earth during the Year of Mercy. Group members have since offered two retreats, attended by dozens of people, on the sacredness of water. “It was very successful in awakening people’s consciousness to the issue of water around the world,” said group member Sister Mary Corlita Bonnarens.

As the reflection group was meeting, Mercy Center in St. Louis replaced its kitchen refrigeration water-cooled units with air-cooled units, saving 2475.88 cubic gallons of water over the first year alone. “The goal was to save the cost and quantity of water and sewage,” said Mercy Center Administrator, Sister Donella Hartman.

Then last year, inspired by the retreats on water, Mercy Health System, based in St. Louis, committed to getting rid of all bottled water at its 44 hospitals and thousands of physician practices and outpatient facilities in Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. Employees were offered reusable cups that they can refill in dining areas and at water bottle refilling stations.

“As a ministry that inherited our mission and heritage from the Sisters, Mercy has a responsibility to echo this concern (for Earth, and particularly water) as part of our efforts toward good stewardship,” an email message to employees explained.

Waste Not, Want Not

Keeping plastic and other recyclables out of landfills is one of the most common sustainable practices in Mercy institutions: 80 percent of survey respondents reported conducting recycling throughout their facilities and 77 percent reported plastic reduction efforts. A much smaller percentage of respondents—28 percent—reported composting operations on their properties.

One of the most ingenious practices can be found at Holy Cross High School on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines, where some students stay after school or return on weekends to separate out biodegradable from non-biodegradable waste. They use the plastic to make bags, throw pillows and ecobricks—1.5-liter plastic bottles stuffed with other plastics until they weigh about 600 grams (roughly one and one-third pounds); the ecobricks are then placed around school gardens to prevent soil erosion. Students are now making ecobricks for a “waiting shed,” a place where they can sit before classes or use as a room for group study.

The school is also trying to limit the use of plastic in its canteen. Staff serve mostly homemade food like fried bananas and pancakes, and eliminated water bottles, plastic straws and candies wrapped in plastic. They now are searching for alternatives to packaged cookies.

“Plastic waste is a big problem in our country and throughout the world,” said Sister Virgencita “Jenjen” Alegado, the school’s directress. “Marine animals have died due to suffocation from swallowing plastic waste, to name just one problem. Thus we find it so urgent that we need to do something.”

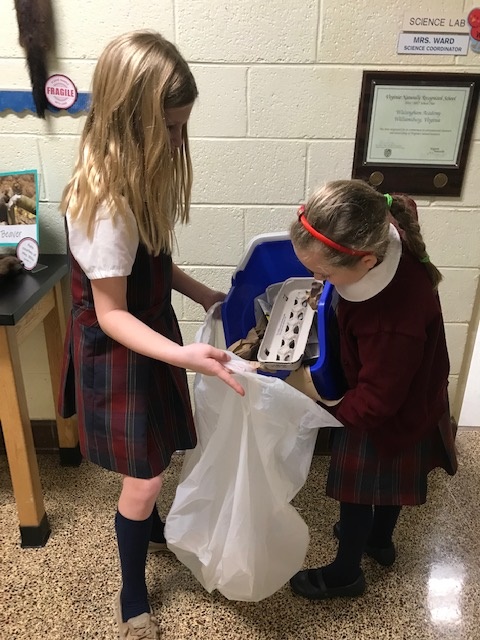

Meanwhile, every Thursday at Walsingham Academy in Williamsburg, Virginia, third-graders on the school’s “green team” collect recycling from the 50 bins placed outside all of the classrooms and offices. They were purchased through a Keep Virginia Clean grant, said Kim Ward, science coordinator for grades K–7. “Protecting our resources and teaching our youth the importance of reducing waste and recycling as many materials as possible is a goal of mine as a science educator,” she said. “The children are eager to make a difference and take their recycling efforts very seriously.”

While composting isn’t as prevalent at Mercy facilities, some convents are leading the way. For example, three sisters living at Casa de Misericordia in Portland, Maine, pay an annual fee to participate in curbside food-waste collection. And in Guyana, Sister Meg Eckart blessed a new composting project on the grounds of Meadowbrook Convent for the Feast of Saint Francis of Assisi last October.

The project partly came out of discussions within the Catholic Church and among the sisters in Guyana in preparation for the Vatican’s Synod on the Amazon, to be held in October.

Said Meg, “Our project has been a small effort for us to live in greater consciousness of our connection to and co-dependence with creation.”

Questions for Reflection

- Do you believe that, as Pope Francis says, “there is a nobility in the duty to care for creation through little daily actions”? If so, which of your actions would you name? Is there another action you want to take so as to further “change the world”?

- Which example shared from the sustainability survey results most inspires you? What first step could you take to explore implementing that effort in your convent, parish, school or place of ministry?

- What support do you need to implement that new action? Contact justice@sistersofmercy.org to connect with any of the people interviewed in this story or to seek other sources of assistance.

- If you live in the U.S. and want to go beyond “little daily actions,” consider becoming a Mercy Earth advocate to speak out for local, state and national climate policies. You may sign up at https://www.sistersofmercy.org/take-action/

Marianne Comfort is justice coordinator for Earth, anti-racism and women at the Institute office. She can be reached at mcomfort@sistersofmercy.org.