Civil Rights, Suffrage and the Untied Shoe of Rosa Parks

share

topics

By Lauren Tyrrell, Institute Communications Office

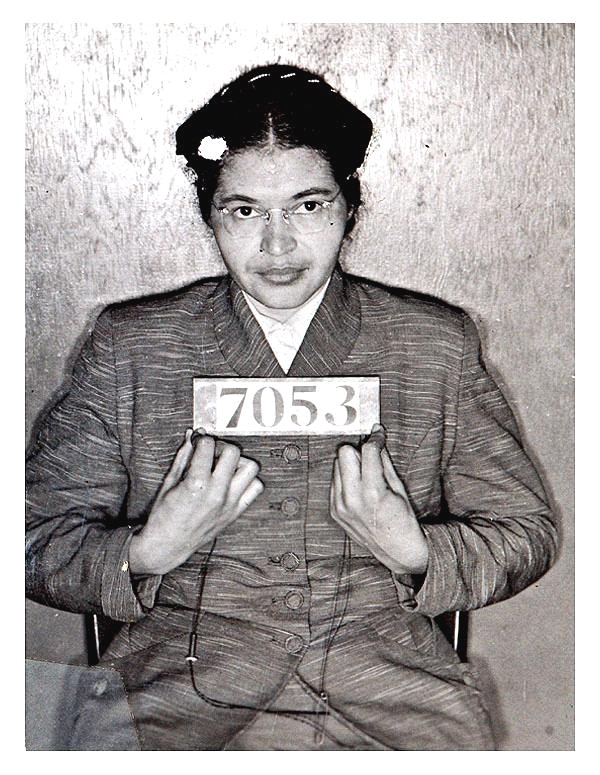

Sister Mary Vernon Gentle remembers as a girl seeing photographs of Rosa Parks. “She always had this distinctive look,” she said. “She was a seamstress by trade, and always had neat-fitting clothes, a pillbox hat and her hair pulled back in bun.” The two women grew up about 100 miles apart—Mary Vernon in Birmingham, Alabama and Parks to the south in Montgomery.

Mary Vernon’s mother, Marie, was a big proponent of the African-American Civil Rights Movement, even before Parks’ bus strike. “Our family was white but segregated from some towns and social places because we were Catholic,” Mary Vernon said. “My mother became close friends with many African American women, who faced far worse segregation.”

Though both women and blacks had suffrage, the voter registration process was designed with the intent to keep nonwhites out of the ballot boxes. “You had to take a test with questions about state and federal government,” Mary Vernon said. “There were five different versions of that test in Alabama, and I don’t know how, but my mother got copies of them.

“After school she and I would go to different neighborhoods, and the women would bring their kitchen chairs out to the curb while my mother taught them the answers to the test. Then we’d drive them to the polling place where they had to take the test, and sometimes they needed to take it a few times, so we’d drive them back again. Sometimes, even if they passed, they had to go back for little things, even just sign their name again, really anything to keep them from registering.

“It was an awful and tortuous process, all that back and forth. But whoever did manage to get their voter ID card, my mother would also drive to the polls on Election Day. She didn’t go around shouting or protesting outside but it was a definite demonstration,” Mary Vernon said.

Seminal moments in the African-American Civil Rights Movement, like Rosa Parks’ arrest on December 1, 1955, helped Mary Vernon to see her mother’s quiet, defiant actions in their larger national context.

Decades later, Mary Vernon was waiting for the last plane out of Atlanta, Georgia to go home to Birmingham. “I was [in the process of becoming a Sister] at the time, and I had been traveling a great deal,” she said. “I was very tired, and it was late. No one was paying much attention to anyone, but I noticed two African American women take seats across from me, one very tall and the other small and feeble. The smaller one was wearing a brown pillbox hat and a simple brown coat, nicely fitted.”

The taller woman left for a time, and Mary Vernon noticed the slight one struggling to tie a shoelace that had come undone. “I offered to help her, and she accepted, so I got up, and as I knelt down to tie her shoe, I noticed on her luggage tag the initials—RP.

“‘Are you Rosa Parks?’ I asked her, suddenly struck by understanding. The slight woman nodded. ‘I didn’t know that when I offered to help,’ I said.

“Rosa Parks took my face in her aged hands and said to me, ‘That means, my dear, that you would do this for anyone.’”

For Mary Vernon the moment was a powerful reminder of mercy’s many forms in our world: caring, kindness and gentleness. Mercy looks past race to see opportunities for love, whether it’s driving disenfranchised women to the ballot, remaining seated on a bus to stand up against systemic injustice or simply tying a shoelace for a struggling stranger in an airport terminal. In the words of Catherine McAuley—“See how quietly the great God does all his mighty works.”