By Jean Stokan

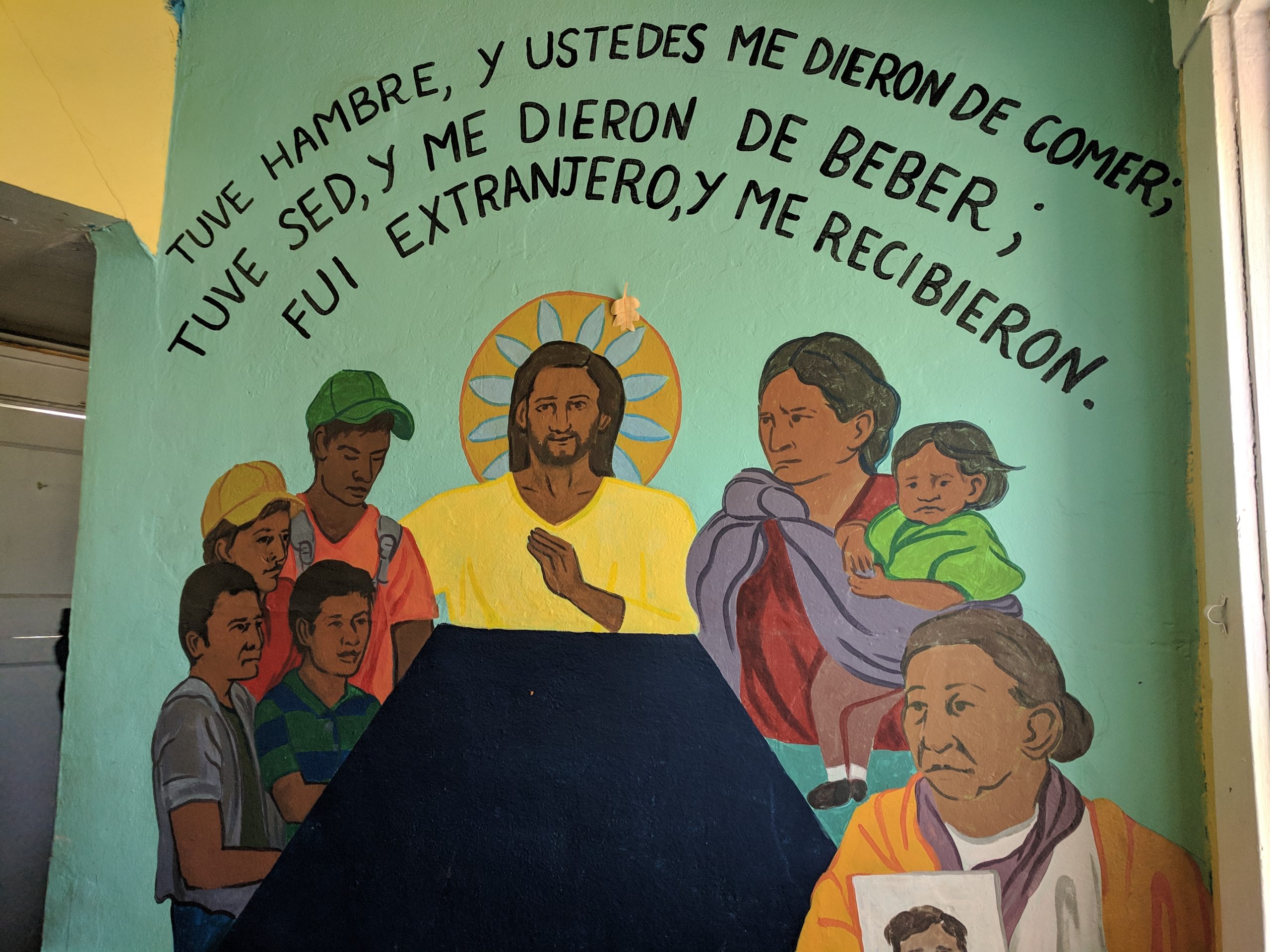

Imagine the Christmas manger surrounded by razor-spiked concertina wire, preventing Jesus and the Holy Family from fleeing Herod, who threatens to kill them.

Having spent Thanksgiving week volunteering at Annunciation House in El Paso, Texas, receiving hundreds of parents and children who had recently crossed the U.S.–Mexico border, I’m haunted by the faces of all the sick children.

At the official border points of entry to the United States, only a trickle of migrants is allowed each week to present their asylum cases to enter, forcing hundreds, if not thousands, to sleep in the extremely dangerous streets on the Mexico side until they are allowed to present themselves.

Desperate families attempt to cross illegally, are apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol officers, and are subsequently held in cells for up to two weeks for processing before being released to the streets with ankle monitors and a date to appear in court.

Annunciation House and other church-related charities along the border have asked that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) release the migrants directly to their shelters. There, migrants have free access to shower facilities, a bed for a few days, and help boarding Greyhound buses to wherever their families are in the U.S. while awaiting their hearings.

The charities have become a “Grand Central Station of Nuns” for the last several months, as Mercy sisters and hundreds of women religious from many congregations have responded to the plea for volunteers. The knowledge that our sisters have been accompanying refugees and immigrants for years—from Maine to California, Chicago to Laredo—inspires me more than words can capture.

During my time on the border, ICE agents released families to Annunciation House; most if not all of the children we saw were ill. We learned from the migrants that our government held them in jail-like spaces for up to two weeks, freezing cold cells they called hieleras, crammed in and forced to sleep on the floor, with minimal food. In other words, treated like criminals even though seeking asylum is not a crime.

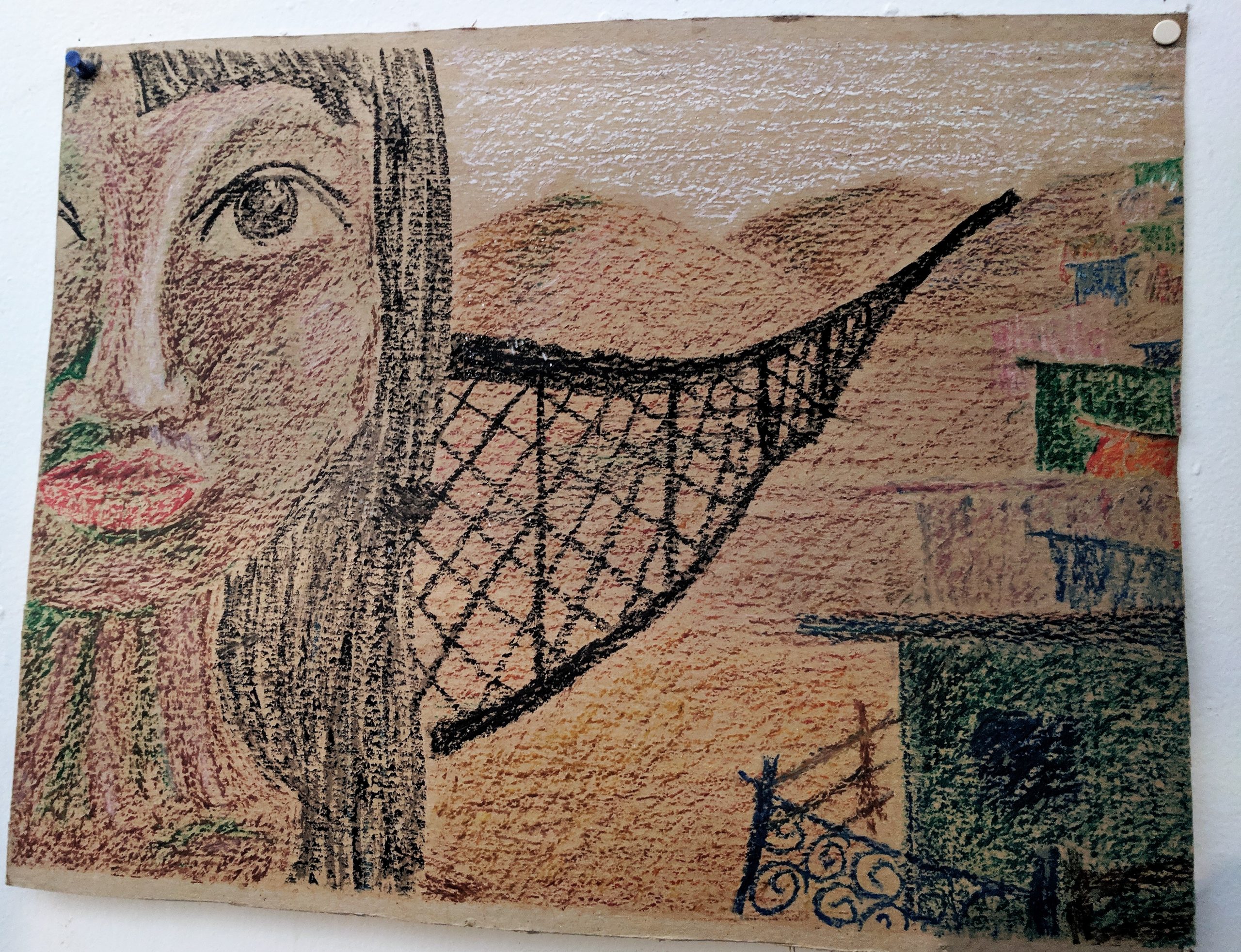

We volunteers did what we could to welcome them with warmth and love, offering a safe place for a few nights, food, and liquid Tylenol for the children’s fevers. At the bus terminal, one Guatemalan woman with a young child broke down in tears in my arms as the Greyhound agent explained to her, in Spanish, that she would have to change buses seven times over her three-day trip to Florida to be reunited with her husband. The woman, who spoke only an indigenous dialect, understood nothing. I did what I could to help her with the transfers, drawing a system of dots on paper and scribbling notes in English and Spanish for her to show to people along the way for help. I don’t know what became of her.

While news media have reported the recent deaths of two migrant children while in U.S. custody, I fear the cost in terms of children’s lives and innocence lost is far greater. Beyond the trauma resulting from the separations last spring and summer of migrant children and parents—some of whom are still not reunited—what haunts me from my time at the border six weeks ago are the faces of sick children with very high fevers.

How many of those terribly sick children, I wonder, died after we got them on the bus? Those stats won’t appear in a Department of Homeland Security report, nor are they likely to be uncovered by the best investigative reporters. How many will soon be deported back to the furnaces of violence only to be killed afterward? How do we justify this treatment of God’s children, at the holidays or at any time? How do we remove the concertina wire from around Jesus’ manger, and from our hearts?

Sign up here to receive action alerts about Sisters of Mercy advocacy efforts, including calls to Congress to deny funding for the border wall. “

If you are interested in learning more, click here.